Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Only at JTS - Halloween = יום העצמות?!

Prof. Visotzky: Jim is a wonderful writer and lecturer

me: I didn't get to hear him at the Seminary last year, but I did hear him lecture last year at Or Zarua, speaking about if there ever was an independent Jewish state before '48.

Prof. Visotzky: Prof. Lieberman once gave a lecture about Yom Haatzmaut. He was talking about how we don't have the phrase יום העצמעות (Independence Day)in Rabbinic Literature. However, we do have the phrase יום העצמות (Day of Bones), referring to Ezekiel's vision of the revived dry bones, which were the house of Israel. And that's how he really saw the state of Israel (how beautiful :)).

Another student walks in: יום העצמות - Is that halloween?

As we like to say, tradition and change...

Sunday, October 18, 2009

2 in 1: Shul-Hopping and Piyyut of The Week

While my writing has been a bit sporadic between the holidays (which were very joyous but also tiring), I was moved to share one of my favorite shulhopping experiences, which I took for the second time with my friend Jonah this past shabbat. Although I have been davening at Hillel a lot over the past year, it would be a shame to not take advantage of the diversity of synagogues and Minyanim in Manhattan, and it's always nice to share it with a friend.

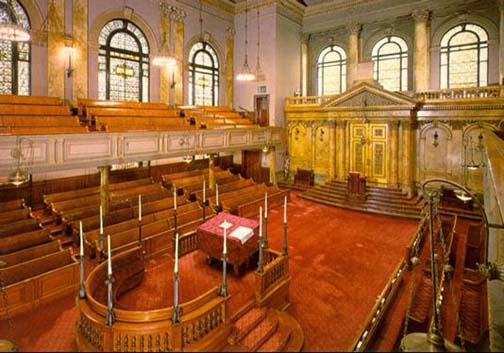

Though I had been there once before at the end of last summer, I returned with Jonah to Congregation Shearith Israel, also known as the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, which has the distinction of being the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States, founded by the first Jews to arrive in New Amsterdam in 1654 after being forced to leave the Colony of Recife, Brazil. The congregation was founded by and still counts most of its membership among Western Sefardim, those who were expelled from Spain (and later Portugal), whose descendants who remained in the West found havens in the Netherlands, and later England and the Americas. I fell in love with the service because of the beauty in every aspect of its orchestration - the sanctuary, one of the most stunning in the country (with a marble Bimah/Ark, golden doors, and Tiffany windows, just to start), unique liturgy and melodies, and the decorum that is unparalleled in most communities of any background.

While last year's visit was also special (and had an amazing extended kiddush for a 95th birthday), I was told that i had to come back on another shabbat when the synagogue's choir would be singing.

When Jonah and I arrived for the start of services at 8:15, there were very few people there, owing to the fact that Birkot Hashachar and Zemirot (known as P'sukei D'zimra by Ashkenazim) take about an hour, and many choose to arrive at some point before shacharit begins. When I attended last time, one of the congregants expaine their custom that one may sit when the Hechal (ark) is open, but that was towards the end of the service. This week, the golden Hechal doors were opened at Barukh Sheamar, early in the service, and the Sifrei Torah were decked out with a rainbow of covers, as opposed to the usual red velvet - based on instructions the siddur, I deduced that it was a Consecration Shabbat, when special features are added to the service in honor of the dedication of one of the Congregation's buildings. After Az Yashir was sung aloud (to a melody that would be familiar to anyone who grew up at Ramah or USY), the Rabbi (whose job is somewhat interchangeable with the Hazzan's at Shearith Israel), arose to the Tebah (reader's desk), and proceeded to lead to congregation in a special piyyut for the Consecration Shabbat known as a reshut, in which the worshippers poetically introduce and ask permission to recite Nishmat, a prayer recited in all tradition on Shabbat and Festivals, describing how 'all living creatures will praise God's name.' Interestingly, dozens of reshuyot, poems written to introduce Nishmat exist, but most have fallen out of use, especially among Ashkenazim. One such Reshut, Tzam'a Nafshi, was originally composed to be recited at this point in the service on Shemini Atzeret, and has instead become a popular zemer sung at the Shabbat table. In this particular Reshut, T'hilot l'el Chai, the author approaches God in reverence and joy ready to worship God, appropriate for its use on a Shabbat of dedication.

Since I couldn't find a recording or lyrics to the poem online (possibly signifying that it is unique to the small Western Sefardi community), I scanned it from the Hebrew English Western Sefardic Siddur (choosing to write my own translation, with no disrespect to the poetic one by Dr. David De Sola Pool), and record the first few verses. Again, the melody was shockingly familiar, and I imagine that others will recognize it as well.

Thanks to God and sweet smelling incense

- The praise of the souls of all living creatures.

You name, Adonai our God, Shall be forever blessed, Our king

- And the spirit of all living flesh, The praise of the souls of all living creatures.

Do not look to my trangressions, and do not remember my iniquities

-And I will sing my songs of praise, The praise of the souls of all living creatures.

Be raised high and acclaimed, King who sits on an exalted throne.

-To you I will give all of my praises, The praise of the souls of all living creatures.

Through this, bring us out of exile, and be quick to fulfill the word of Your prophet,

-To annoint the son of Jesse, with the thanks of the souls of all living creatures.

Bring us to Your [holy] city, and reestablish Your Temple,

-There I will offer my sacrifices, and there I will sing Nishmat Kol Chai.

After the rabbi returned to his seat on the bench in the center Bimah (see above photo), I was (pleasantly) awoken as choir began to chant Nishmat from a loft above the Hechal. As with the rest of the service they sang without any microphones, but Jonah noticed a vent intuitively built into the wall which carried the sound down to the main floor. Unlike in the Ashkenazi cantorial/choral tradition, the choir does not really chant any extended 'pieces', but chants the lines of service in a back and forth (antiphony) with the congregation and leader, with many lines sung in a call and response. After taking the Music Humanities course at Columbia last semester, I have a greater appreciation for the baroque style of the Western Sefardi Nusah, with its greater proportion of singing in a major key than Ashkenazi Nusah.

As with last time, I again enjoyed the rest of the service, with the beauty of the pomp and circumstance which raises Tefilah to a new level (though I still enjoy more infomal davening as well). It was amazing to think during the prayer for the country (which was followed by the prayer for Israel), that a version of this prayer has been recited by the forebears of these congregants since the founding of the country in 1776, before which a prayer was surely recited for the Dutch and British monarchies, respectively. A hallmark of Shearith Israel's tradition is that each man who receives an honor, including the boy who held the bells which adorn the Torah, must wear a hat of some sort, whether it is a bowler, top-hat, or the special cap worn by the clergy. Even the announcements have a liturgical plasce in the order of the service, as they are marked in the siddur following the blessing of the new month (or the Haftarah blessings), after which the Rabbi/Hazzan intones the verse, יהי חסדך ה' עלינו כאשר יחלנו לך 'May God's grace be upon us as we have placed our trust in Him,' signifying the hope that the community's activities are in accordance with God's will. Although the entire service was recited in Hebrew (and mostly aloud, as the Musaf Amidah was recited by the entire congregation with the Hazzan, there being no silent devotion), I was again fascinated by the Hazzan preceding the recitiation of Kiddush with Isaiah 58:13-14 in English. While I would like to learn more about this custom, my guess is that it is an old tradition, as the congregation's leaders directly appeal to them to honor and keep the Sabbath holy as they return home from the synagogue.

I look forward to my next visit Shearith Israel, as well as other Congregations in Manhattan and beyond which I hope to experience. I hope that others will join me in the fine tradition of shulhopping, experiencing how Jewish communities hailing from around the world and expressing a variety of beliefs, give meaning and honor to the act of worshiping God.

Wednesday, September 23, 2009

Yom Kippur: A time of closeness to God - Piyyut of the Week, L'cha Eli T'shukati

Among the most moving themes of the liturgy of the day is that of closeness to God. Because we are confident that we will be forgiven on this day, the common Ashkenazi melody for the Vidui (confessional) is so happy, and in some communities, dancing takes place during some of the Piyutim, especially Mar'eh Kohen (How beautiful was the High Priest) after the description of the Temple service in Musaf. At least for Ashkenazim, this is the only day of the year that the line Barukh Shem Kevod following the Shema is recited aloud as it used to be in the Temple, and not in our usual undertone.

One of my favorite websites, Piyut.org.il, features the text and melodies for Jewish liturgical poety from across the spectrum of time, place and tradition, spanning from Greece to France and America to Tunisia. The featured piyyut this week is L'cha Eli T'shukati ascribed to the one of the famous Spanish-Jewish poets, Avraham Ibn Ezra or Yehuda Halevi. Although I had never heard of it before, I was drawn both by the words, in which the individual confesses to God as a lover would for their mate. It contains themes of both love and desire, as well as a poeticized version of the confession, going through our alphabetical laundry list of sins.

Again although I had never heard of this stirring piyyut before, it is one of the most well-known in the Sefardic tradition, recited throughout the world in their tradition as Jews gather in the synagogue to prepare for the recitation of Kol Nidrei. On that note, it is especially significant that in their custom, the dry, legal declaration of Kol Nidrei is preceded by an moving and emotional expression of our feelings of closeness to God which we will experience over Yom Kippur. The following translation is only of a selection from the very long piyyut; if you understand Hebrew, I encourage you to look at the full text, including the detailed confessional here. Below the text and translation, enjoy the music video of the piyyut by popular Israeli artist Meir Banai, whose rendition so moved me. If you are not moved by your high holy day services, imagine this melody as you prepare for this period of closeness, the holiest twenty five hours of the year in which we celebrate our passionate love for God, 'for we are Your children, and You, our parent.'

G'mar Hatima Tova! May you be inscribed for a happy and healthy year.

| For You, God is my passion; in You is my love and affection. Yours are my heart and organs, to You are my soul and spirit. Yours are my hands and legs, and from You are my very thoughts. For Yours are my blood and limbs, and my flesh and my essence. Yours are my eyes and my ideas and my shape and creation. To You I owe my spirit, my strength, and my hope and trust is in You. To You I will yearn and I cannot compare, until my darkness will shine brightly. To You I will shout, and to You I will cling until my return to my land. To You is the kingship and pride, the direction of my praise. From You is help at the time of need, be my help in my distress. | בְּךָ חֶשְׁקִי וְאַהֲבָתִי לְךָ רוּחִי וְנִשְׁמָתִי וּמִמָּךְ הִיא תְּכוּנָתִי וְעוֹרִי עִם גְּוִיָּתִי וְצוּרָתִי וְתַבְנִיתִי וּמִבְטַחִי וְתִקְוָתִי עֲדֵי תָּאִיר אֲפֵלָתִי עֲדֵי שׁוּבִי לְאַדְמָתִי לְךָ תֵאוֹת תְּהִלָּתִי הֱיֵה עֶזְרִי בְּצָרָתִי | לְךָ אֵלִי תְּשׁוּקָתִי לְךָ לִבִּי וְכִלְיוֹתַי לְךָ יָדַי לְךָ רַגְלַי לְךָ עַצְמִי לְךָ דָמִי

לְךָ רוּחִי לְךָ כֹחִי

לְךָ אֶזְעַק בְּךָ אֶדְבַּק

לְךָ עֶזְרָה בְּעֵת צָרָה |

Sunday, September 6, 2009

Piyyut of the week: We come finally, with trepidation -- במוצאי מנוחה - As Shabbat Leaves Us

(As an aside, the differing lengths of time for which Selichot are recited is not based on greater or lesser piety, but two different explanations. Sefardim recite these prayers for forty days, paralleling the time that Moses spent on Mount Sinai petitioning to God before receiving the second set of the Aseret Hadibrot. According to tradition, he ascended on Rosh Hodesh Elul and descended on Yom Kippur, at which point God granted forgiveness to the people. The Ashkenazi custom is based on the idea of having a series of ten days of fasting leading up to Yom Kippur. Since there are four days during the Aseret Y'mei Teshuva (Ten days of Repentance) when it is forbidden to fast - the two days of Rosh Hashanah, Shabbat Shuvah, and Erev Yom Kippur, these four days of fasting would be brought forward, prior to Rosh Hashanah. The tradition of the ten days of fasting, on which we now recite selichot even if we do eat, is combined with the idea of the end of Shabbat being a time of special favor before God. Thus, Ashkenazim begin to recite Selichot on the Saturday night at least four days before Rosh Hashanah.)

Although Selichot are generally recited before dawn, on this first night of Ashkenazi selichot, the practise has grown up to recite the service close to midnight. Some shuls offer special lectures or educational programs prior to selichot, and others accompany the service with a cantor, choir (or even a band at the Carlebach Shul). At the center of each day's order of Selichot is the piyyut known as a pizmon, or chorus, since each stanza of this genre concludes with a repeating chorus.

On the first night of Selichot, the featured pizmon is entitled B'motzaei M'nucha, As Shabbat Leaves Us. It is appropriate on many levels at be recited/sung at this point in the season. Besides for speaking of the ending of Shabbat, the poem also contains many images of the Jewish people standing in reverence before God. This is especially appropriate as it is very often recited close to the week of Parashat Nitzavim, which opens with the verse, "You, all all of you are standing before Adonai your God, the leaders of your tribes, elders, officials, and each individual in Israel." (Devarim 29:9). I hope you enjoy the following translation and commentary on this beautiful, moving (and anonymous) poem which has taken such a central place in the Ashkenazi liturgy

|

|

| ||||

|

To hear the pleasantness and the prayer. |

| ||||

| To hear the pleasantness and the prayer. |

| ||||

| To hear the pleasantness and the prayer. |

| ||||

| To hear the pleasantness and the prayer. |

| ||||

| To hear the pleasantness and the prayer. |

| ||||

| Bring justice to those who cry out to You, O maker of wonders Hear now their petition, God, Lord of Hosts To hear the pleasantness and the prayer. |

| ||||

|

To hear the pleasantness and the prayer. |

|

The paytan who composed this Pizmon most likely lived in the later piyyut period, as the poem features a rhyme in each stanza, epithets such as those referring to Isaac and Israel, and vocabulary unique to piyyut. Part of what makes the words so stirring and appropriate for this first night of selichot, is the tying together of a number of themes: Our approaching God late at night - a time of favor, our doing so with sweet words and melodies, and in contrast our appeal to God despite our unworthiness and sinfulness. As this Pizmon speaks in somewhat general tones about these ideas, it fittingly introduces the themes that will be discussed and grappled with through the ever-changing piyyutim of the Ashkenazi liturgy.

I hope that you take the time to appreciate the beauty of this ancient, yet timely poetry, especially if you attend any of the various selichot services that will take place around the world this Saturday Night, במוצאי מנוחה, at the close of Shabbat.

As a treat I hope readers will enjoy this rendition of B'motzaei M'nucha by Hazzan Moshe Stern and choir from the Great Synagogue in Tel Aviv: